Warning: This post is full of swears. It’s been a total shit day.

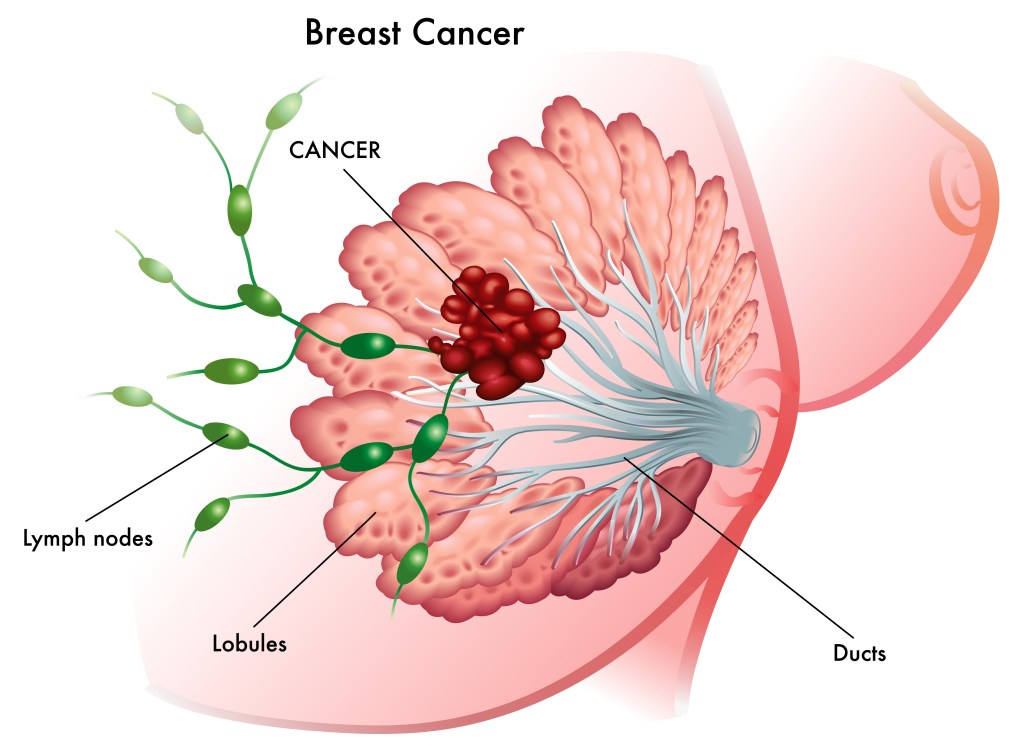

Getting “normal” annual mammograms after breast cancer is nerve wracking. I get that. Literally. Today was my second routine mammogram after completing surgical and radiation treatments. What (I’d hoped) would be an hour long visit followed by an, “All clear! Go, and live happy,” turned into a 3 1/2 hour long ordeal that consisted of FOUR FUCKING IMAGING sessions, an ultrasound, and scheduling another biopsy.

This is fucking bullshit.

For those of you who’ve been there, done that, bought the T-shirt (that reads, “Of Course They’re Fake – The Real Ones Tried to Kill Me”), you get it. I’ve had several survivors in my circle offer support, well-wishes, and cat memes, and I’m grateful. For those of you who haven’t been there (and I hope you never are), let me give you some background. At the time of this blog post I’ve had:

Six biopsies (last time was a charm with the Big C)

Two lumpectomies (one to remove a benign papilloma and the other to remove cancer – followed by oncoplastic reconstruction involving a reduction and lift)

Implantation of TWO Savi Scout devices to mark my tumors (this was mammography assisted, meaning I was in fucking compression while two GINORMOUS needles the size of small screw drivers were stuck into my left boob and I actually saw the tip of one come out the other side)

Twenty-eight rounds of radiation on my left boob – crispy bacon, anyone?

And a partridge in a pear treeeeeeee!

You’d think that would be enough. Seriously. But, alas, not for me. Whenever I go in for routine checks, I get the extra imaging, the call backs, the ultrasounds, and the biopsies. My breast are pincushions. It’s not fun.

Today’s visit started out well enough. I went into the room with my lovely robe, wiped off the deodorant I’d put on (because I forgot that I wasn’t supposed to use any), flopped out one boob, then the other, let the nice nurse get to second base while positioning my boobs, had my (first) mammogram scans and returned to the waiting room. Aside from being a bit sore (the left boob, cancer boob, is harder than the right thanks to radiation and it’s pretty uncomfortable in the old squeezy squeezy machine), I was content. I texted the lab to tell them I hoped I’d be in soon and then enjoyed some Facebook and Twitter time while waiting. I also had in-room entertainment in the form of a brash and bawdy lady who was Skyping – loudly – and having the kind of inappropriate conversation that you kind of want to film because it’s disturbingly awesome and no one will believe you unless you record it. All in all, not too shabby.

Then, they called me back. Just need a few more images, they told me. Nothing to be concerned about. I groaned, but was still okay. Considering my normal experiences with mammograms, this was a drop in the boob bucket. I got squished, got sore, and was escorted back to the waiting room filled with other women in those high fashion robes you get when you have to get your boobies squished. My entertainment was gone, and I missed her terribly, but I was slightly more concerned with the passage of time.

I mean, I did have work to do.

They called me back again. This time, the nurse (BTW, they’re all wonderful and I don’t fault them for any of this) explained that they’d found a spot. It was of concern because they hadn’t seen it on my previous post-treatment scans. They hadn’t seen it, because apparently this time the nurse was so good that she got images closer to the chest wall and they were seeing new areas for the first time. On the one hand, go nurse! Great technique!

On the other hand, WTF is the spot? Is it something I should worry about? We don’t know how old/new it is because we haven’t seen it before. Seriously, I’m two years out. I shouldn’t have a recurrence.

They needed another set of scans to make sure it was real, especially since they’d seen it only in one image/plane. So, for the third time, back in the boob vise for a trip to fuck that hurts land.

I go back to the waiting room. And…I’m called back for – I shit you not – ANOTHER round of images. This time they let me stay in the room with the owie machine while I wait for the radiologist to have a peek. Shortly thereafter, they tell me, as I predicted by this point, it was ultrasound time!

I’ve had plenty of ultrasounds.

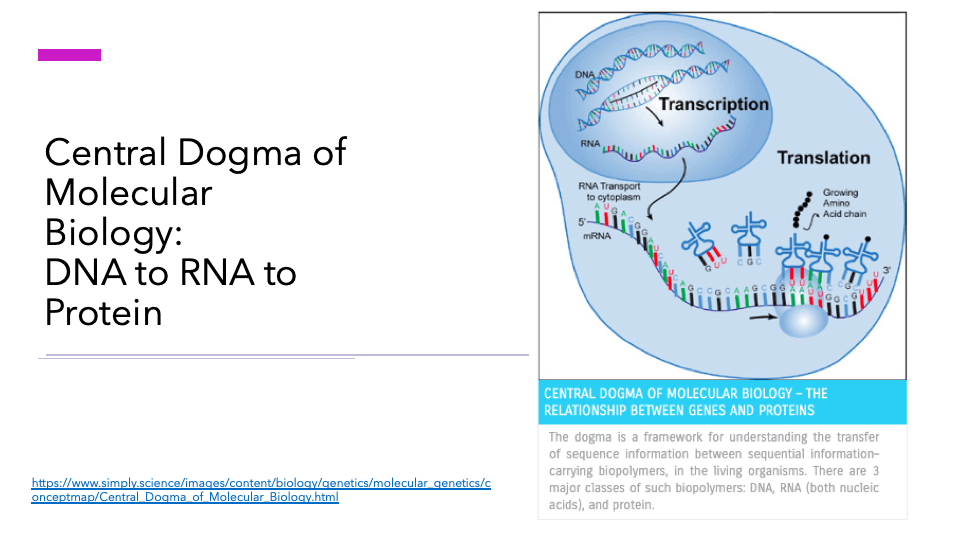

As is my standard practice, I asked if I could see the screen, explaining that I’m a breast cancer researcher. Yeah, I got breast cancer, too, the irony isn’t lost on me. Yes, I’ve become more passionate about my research and am getting into advocacy, too. Sure, I’d love to see the mammogram image of the spot in question. Interesting (i.e. I have no idea if what I’m seeing is bad or not – then again, neither does anyone else or I wouldn’t be here).

I flopped out my left boob, the one I’d called a pain in my ass during my 4th time in the booby squeeze machine (and made the nurse giggle snort), put my left hand over my head, got the ultrasound goo smeared over my bad boob, and then the nurse commenced with the scavenger hunt via wand. And she wanded. And she wanded. And she wanded.

My arm was getting a little numb, and I was a bit concerned that she wasn’t taking pictures, but I just chilled. Then, she told me she wasn’t sure anything she was seeing matched the spot on the mammogram. So she grabbed the radiologist, who came in, goo-ed me up, and wanded. And wanded. And wanded.

The radiologist laid it out for me. They’d seen this spot, which was uniform in shape, an oval, and was most likely nothing to be concerned about – fat necrosis, an artefact of scarring, or a benign lesion. Given that it was in my bad cancer boob, she recommended a biopsy. And since they couldn’t find it by ultrasound, I would need a mammogram guided biopsy.

That’s exactly as sucktastic as it sounds. I will be put in (terribly uncomfortable) mammogram compression and stay there while someone jabs a fucking biopsy needle into my boob. Yes, I’ll have lidocaine, but that’s not going to help with the squeezy squeezy or the HORROR!

And, while I wait 9 days for the biopsy and another 5-7 days for the results, I’ll be stressed out. This is the reality for survivors. We’re ALWAYS nervous with scans, and it’s compounded when extra examinations are needed. It’s terrifying. Yes, rationally I understand that the odds of finding another tumor are extremely low, but the fear is visceral and always there. I’m worried it always will be. Most days, I’m upbeat and snarkily positive, but not today.

Some days, the best you can do is just hope for better tomorrow.