I’m thrilled and delighted to announce that I’ve signed with Barbara Collins Rosenberg of The Rosenberg Group to represent a nonfiction project based on my experience as a breast cancer researchers who was diagnosed with breast cancer! My goal is to expand on what I do here, providing accessible science with a healthy dose of humor and hope. Here’s a preview from my proposal:

Can I talk to you about my personal relationship with my breasts?

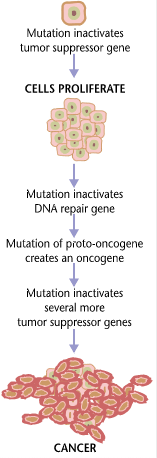

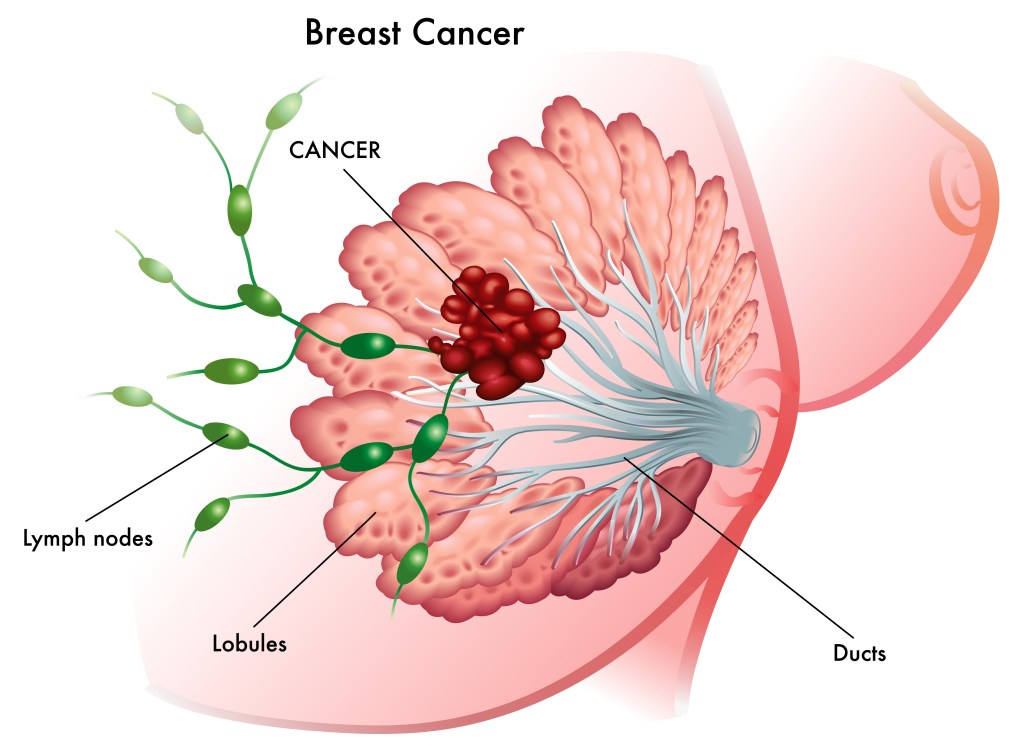

I’ve spent twenty years working as a biomedical breast cancer researcher. Then, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. I thought I knew breast cancer before it whacked me upside my left boob and left me bleeding on the curb of uncertainty. The purpose of this book is to share my personal adventure with breast cancer, from the laboratory bench to my own bedside, and to provide accessible information about breast cancer biology for non-scientists. I say adventure, because I’d rather think of it as action movie with some really cool side quests instead of another tragedy-to-triumph saga. I’m not big on sagas. I am big on kickass intellectual badassery, pathological nerdiness, and talking about my sweet, sweet rack.

Why do we need another cancer memoir? In a sea of inspirational stories, celebrity survivor stories and physician memoirs that bring a clinical perspective, nothing I’ve found in the current market tackles breast cancer through the lens of a breast cancer researcher who became a survivor. We live in an age of fake news and pseudoscience, made worse by the pervasive anti-intellectual and anti-science political culture gripping the United States and much of the world. The Internet and social media are plagued by scammers selling “alternative medicine” and woo woo “cures” for cancer. Through Talking to My Tatas: A Breast Cancer Researcher’s Adventure With Breast Cancer And What You Can Learn From It, I offer accurate, evidence-based science that is accessible to laypersons, including the more than three hundred thousand individuals diagnosed with breast cancer every year*, their caregivers, and their loved ones.

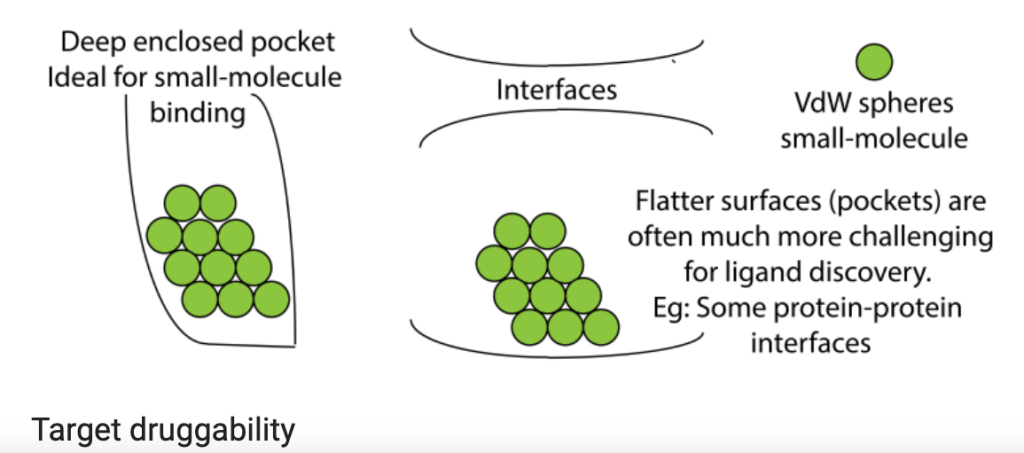

Knowledge is power, and lack of it can lead to overtreatment, unnecessary pain and suffering, and can even be deadly. By demystifying the process from mammograms, biopsies, pathology and diagnostics, surgical options, tumor genomic testing, and new treatment options, I aim to offer hope in a story intended to blend the humor and delivery style of Jenny Lawson’s Let’s Pretend This Never Happened (A Mostly True Memoir) with the integrity and scientifically sound beauty of Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer.